Ending

Poverty: How We Can Make God, and Each Other, Happy

by

Rev. Paul J. Bern

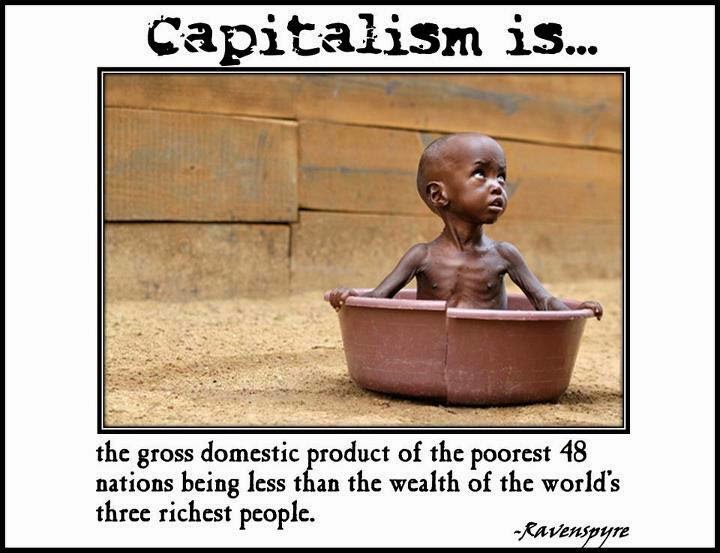

With

about 99% of the wealth in America in the hands of a little over 1%

of the population, the US has a bigger and wider gap between the

richest 5% of American money earners and big business owners and the

remainder of working Americans than there is in many supposedly

“third world” countries. The widespread and systemic unemployment

or underemployment that currently exists in the US job market is no

longer just an economic problem, it has – here in the early 21st

century – become a civil rights issue. The US job market has been

turned into a raffle, where one lucky person gets the job while

entire groups of others get left out in the cold – sometimes even

literally. I am vigorously maintaining that every human being has the

basic, God-given right to a livelihood and to a living wage. Anything

less becomes a civil rights violation and therefore that jobless

person(s) are victims of systemic discrimination. And so I state

unreservedly that restarting the civil rights era protests,

demonstrations, sit-ins and the occupation of whole buildings or city

blocks is the most effective way of addressing the rampant inequality

and persistent economic hardship that currently exists in the US.

Fortunately,

this has already started here in the US, with the advent of the

protests for Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown and Eric Garner. But these

protesters are behind the curve. Because before them there was Occupy

Wall St., “we are the 99%” and Anonymous. And before them there

was the Arab Spring in Egypt, the summer of 2011 in Great Britain and

Greece in Europe, and Libya, Syria and Gaza in the Middle East. So

from a political standpoint, the current crop of protesters here in

the US had some catching up to do. But that was before the rest of

the world got on board protesting globally for the three murdered

Americans in Florida, Missouri and New York. So now, like an echo

from the fairly recent past, the protests over police violence has

echoed across the globe and is still reaching a crescendo. The least

common denominator to all this rage in the streets is that of being

economically disadvantaged. People everywhere find themselves

surrounded by wealth and opulence, luxury and self-indulgence, while

they are themselves isolated from it. It is one thing to be rewarded

for success and a job well done. But it's an altogether different

matter to have obscene riches flaunted in your face on a daily basis

just because someone can. I think what we really need to do is find a

way to end poverty. I can sum up the answer in one word: Education.

Otherwise those who are poor

will always remain so.

Who’s

responsible for the poor? Back in the reign of the first Queen

Elizabeth, English lawmakers said it was the government and

taxpayers. They introduced the compulsory “poor tax” of 1572 to

provide peasants with cash and a “parish loaf.” The world’s

first-ever public relief system did more than feed the poor: It

helped fuel economic growth because peasants could risk leaving the

land to look for work in town. By the early 19th century, though, a

backlash had set in. English spending on the poor was slashed from 2

percent to 1 percent of national income, and indigent families were

locked up in parish workhouses. In 1839, the fictional hero of Oliver

Twist, a child laborer who became a symbol of the neglect and

exploitation of the times, famously raised his bowl of gruel and

said, “Please, sir, I want some more.” Today, child benefits,

winter fuel payments, housing support and guaranteed minimum pensions

for the elderly are common practice in Britain and other

industrialized countries. But it’s only recently that the right to

an adequate standard of living has begun to be extended to the poor

of the developing world.

In

an urgent 2010 book, “Just Give Money to the Poor: The Development

Revolution from the Global South”, three British scholars show how

the developing countries are reducing poverty by making cash payments

to the poor from their national budgets. At least 45 developing

nations now provide social pensions or grants to 110 million

impoverished families — not in the form of charitable donations or

emergency handouts or temporary safety nets but as a kind of social

security. Often, there are no strings attached. It’s a direct

challenge to a foreign aid industry that, in the view of the authors,

“thrives on complexity and mystification, with highly paid

consultants designing ever more complicated projects for the poor”

even as it imposes free-market policies that marginalize the poor. “A

quiet revolution is taking place based on the realization that you

cannot pull yourself up by your bootstraps if you have no boots,”

the book says. “And giving ‘boots’ to people with little money

does not make them lazy or reluctant to work; rather, just the

opposite happens. A small guaranteed income provides a foundation

that enables people to transform their own lives.”

There

are plenty of skeptics of the cash transfer approach. For more than

half a century, the foreign aid industry has been built on the belief

that international agencies, and not the citizens of poor countries

or the poor among them, are best equipped to eradicate poverty.

Critics concede that foreign aid may have failed, but they say it’s

because poor countries are misusing the money. In their view, the

best prescription for the developing world is a dose of discipline in

the form of strict “good governance” conditions on aid. According

to The World Bank, nearly half the world’s population lives below

the international poverty line of $2 per day. As the authors of Just

Give Money point out, that’s despite decades of top-down,

neo-liberal, extreme free-trade policies that were supposed to “lift

all boats.” In Africa, South Asia and other regions of the

developing “South,” the situation remains dire. Every year,

according to the United Nations, more than 9 million children die

before they reach the age of 5, and malnutrition is the cause of a

third of these early deaths.

Just

Give Money argues that cash transfers can solve three problems

because they enable families to eat better, send their children to

school and put a little money into their farms and small businesses.

The programs work best, the authors say, if they are offered broadly

to the poor and not exclusively to the most destitute. “The key is

to trust poor people and directly give them cash — not vouchers or

projects or temporary welfare, but money they can invest and use and

be sure of,” the authors say. “Cash transfers are a key part of

the ladder that equips people to climb out of the poverty trap.”

Brazil, a leader of this growing movement, provides pensions and

grants to 74 million poor people, or 39 percent of its population.

The cost is $31 billion, or about 1.5 percent of Brazil’s gross

domestic product. Eligibility for the family grant is linked to the

minimum wage, and the poorest receive $31 monthly. As a result,

Brazil has seen its poverty rate drop from 28 percent in 2000 to 17

percent in 2008. In northeastern Brazil, the poorest region of the

country, child malnutrition was reduced by nearly half, and school

registration increased. South Africa, one of the world’s biggest

spenders on the poor, allocates $9 billion, or 3.5 percent of its

GDP, to provide a pension to 85 percent of its older people, plus a

$27 monthly cash benefit to 55 percent of its children. Studies show

that South African children born after the benefits became available

are significantly taller, on average, than children who were born

before. “None of this is because an NGO worker came to the village

and told people how to eat better or that they should go to a clinic

when they were ill,” the book says. “People in the community

already knew that, but they never had enough money to buy adequate

food or pay the clinic fee.”

In

Mexico, an average grant of $38 monthly goes to 22 percent of the

population. The cost is $4 billion, or 0.3 percent of Mexico’s GDP.

Part of the money is for children who stay in school: The longer they

stay, the larger the grant. Studies show that the families receiving

these benefits eat more fruit, vegetables and meat, and get sick less

often. In rural Mexico, high school enrollment has doubled, and more

girls are attending. India

guarantees 100 days of wages to rural households for unskilled labor,

paying at least $1.25 per day. If no work is available, applicants

are still guaranteed the minimum. This modified “workfare”

program helps small farmers survive during the slack season. Far from

being unproductive, the book says, money spent on the poor stimulates

the economy “because local people sell more, earn more and buy more

from their neighbors, creating the rising spiral.” Pensioner

households in South Africa, many of them covering three generations,

have more working people than households without a pension. A

grandmother with a pension can take care of a grandchild while the

mother looks for work. Ethiopia pays $1 per day for five days of work

on public works projects per month to people in poor districts

between January and June, when farm jobs are scarcer. By 2008, the

program was reaching more than 7 million people per year, making it

the second largest in sub-Saharan Africa, after South Africa.

Ethiopian recipients of cash transfers buy more fertilizer and use

higher-yielding seeds.

In

other words, without any advice from aid agencies, government, or

nongovernmental organizations, poor people already know how to make

profitable investments. They simply did not have the cash and could

not borrow the small amounts of money they needed. A good way for

donor countries to help is to give aid as “general budget support,”

funneling cash for the poor directly into govenment coffers. Cash

transfers are not a magic bullet. Just Give Money notes that 70

percent of the 12 million South Africans who receive social grants

are still living below the poverty line. In Brazil, the grants do not

increase vaccinations or prenatal care because the poor don’t have

access to health care. A scarcity of jobs in Mexico has forced

millions of people to emigrate to the U.S. to find work. Just Give

Money emphasizes that to truly lift the poor out of poverty,

governments also must tackle discrimination and invest in health,

education and infrastructure.

The

notion that the poor are to blame for their poverty persists in

affluent nations today and has been especially strong in the United

States. Studies by the World Values Survey between 1995 and 2000

showed that 61 percent of Americans believed the poor were lazy and

lacked willpower. Only 13 percent said an unfair society was to

blame. But what would Americans say now, in the wake of the housing

market collapse and the bailout of the banks? The jobs-creating

stimulus bill, the expansion of food stamp programs and unemployment

benefits — these are all forms of cash transfers to the needy. I

would say that cash helps people see a way out, no matter where they

live.

No comments:

Post a Comment